Forward-thinking insights focused on a more sustainable tomorrow.

Helping Coastal Clients Become Future-Focused: Oyster Surveys Provide Clues to Health of Aquatic Ecosystems

Whether he’s studying oyster beds, searching for underwater springs, or devising techniques for the early detection of Covid in wastewater, Adam is in his element—outdoors. Here’s his story:

I’ve been an outdoor enthusiast and student of the natural world since I was a kid, hunting and fishing with my dad. I’ve always been a keen observer, and I learned a lot spending time outdoors with my family. But when I began pursuing a computer engineering degree at Penn State University, I realized that I should turn this passion into a career. I decided I didn’t want a desk job my whole life, so I changed my major to Wildlife and Fishery Science, and it’s one of the best decisions I’ve made.

After a few years of working as a research scientist, fisheries observer, and science teacher, I lined up an informational interview at VHB, and a few weeks later a position opened. Now, nearly 17 years later, I am working out of VHB’s Sarasota office, am always busy, and certainly never bored. My specialty is in hydrology and water resources, and that allows me to study a range of topics, including estuary health, wastewater, and underwater spring outflows.

Getting My Hands Dirty

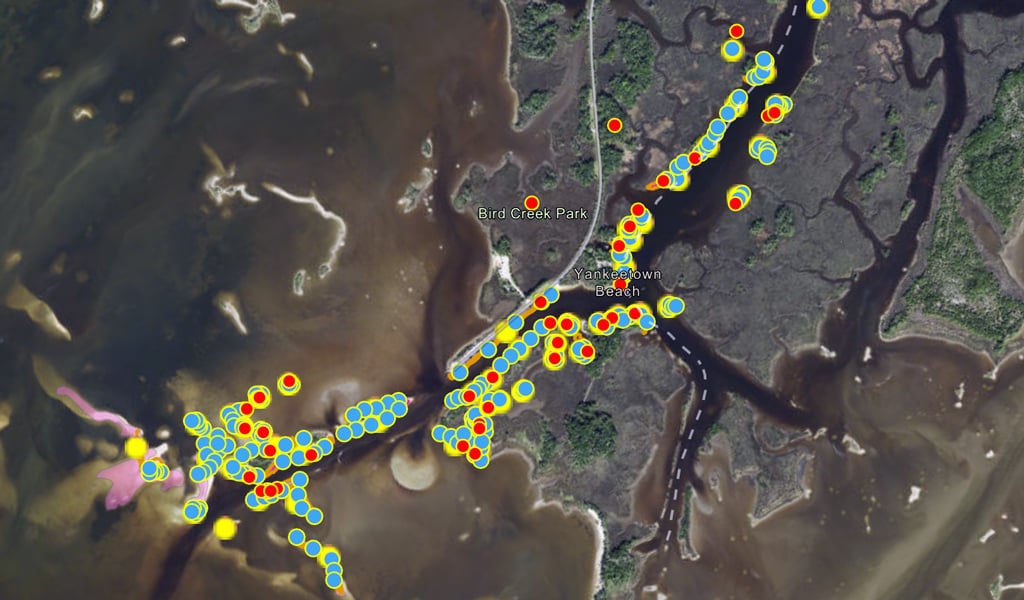

A lot of my role includes being directly in the field, in a variety of settings and working through a multitude of weather conditions. One of the projects VHB worked on recently was an oyster survey we completed for the Southwest Florida Water Management District (SWFWMD). It even made the news! This work helped our clients understand the health of local estuaries and the impact of environmental changes on our coastal community. It was a dirty job that required us to crawl through muck to survey the oyster beds, but I was in my element and happy. I served as field team lead and worked closely with our Southeast Region Environmental Services Leader, Gary Serviss; Environmental Scientist, Matthew Calhoun; and Biologist, Casey Dunn, from our Atlanta office.

Oysters are an indicator species, meaning they provide clues about how an aquatic ecosystem is doing overall. This was our first oyster survey, so figuring out the methodology was an enjoyable challenge. While on site, at least one person traced the boundaries of the oyster beds and took qualitative notes. Two people assessed one quarter-meter squared quadrats, counted the oysters, and measured them with calipers. We found certain areas where they were thriving, and others where the population had declined significantly, probably due to salinity shifts.

Another fun project in the field for SWFWMD included monitoring the outflows of the numerous springs that feed Kings Bay, north of Tampa, and serve as the head waters for the Crystal River. Kings Bay is home to manatees year-round and is the only place in the U.S. where people can legally interact with them in the wild.

“When I reflect on these projects, I am reminded of how fulfilling it is to be in such a unique position that helps clients with environmental concerns as they plan for long-term disaster management, population growth, and infrastructure improvements.”

This was the first time anyone had monitored these springs. We had to design the protocol and equipment to measure outflows that are submerged 15-20 feet. We wanted to know how much water was flowing into the Crystal River and where it was coming from.

First, we dove down with scuba gear looking for vents based on underwater maps of known springs. We also had to conduct conversations with local residents due to this being the first time these springs had been monitored. After locating about 70 springs, including a few that had never before been identified, we adapted flow-measurement devices to record discharge through the spring vents.

The Kings Bay project required extensive underwater work—first locating 70 springs, many of which had never before been unidentified, and then measuring and recording the volume of water each spring discharged.

Innovative Solutions with Technology at the Core

I’ve grown up with technology and have always been an enthusiast, which has translated to me being a big advocate for mobile data collection at VHB. My team has helped advance this throughout the past 15 years. We caught on to the trend early and helped to pioneer the use of GIS, iPads, and other tools with some big initiatives. It takes a bit more setup at the beginning, but you make it up in quality control for data collection. Plus, we now have an interface that anyone can access for data tracking and documentation versus illegible field notes.

Another novel, public health-focused project our VHB Tampa office worked on was sampling wastewater for Sarasota’s Ringling College as means of early Covid-19 detection. This was a really interesting project. It required innovative solutions to safely access the college’s sanitation system, devise a monitoring protocol, and reliably collect the data Ringling needed to help prevent campus outbreaks. We helped the College as an early adopter of this method of detection and were also featured on the local news.

Automatic samplers were programmed to collect wastewater samples from the Ringling College campus sanitation systems over a 24-hour period for the early detection of COVID-19.

When I reflect on these projects, I am reminded of how fulfilling it is to be in such a unique position that helps clients with environmental concerns as they plan for long-term disaster management, population growth, and infrastructure improvements. There is truly never a dull moment in this role, and it’s been rewarding to see the industry shift and change over the years, adapting to new technologies and innovatively pivoting when faced with unpredictable circumstances.

Have any questions for me about the projects described above, or our use of technology? Reach out for more information by emailing me or connecting on LinkedIn.